In Between Soft and Hard-Core: Japanese Pink Movies

While pink colour is generally associated with love, kindness, romance, and femininity, Pink Movies (or pinku eiga in Japanese) are inspired by the dark side of human sexuality and lust.

Eroduction films (eradakushion eiga) or “three-million-yen-films” (sanbyakuman eiga) were erotic movies produced and distributed by small, independent studios. In 1963, a journalist from Naigai Times coined first the term Pink Movies, which would be used in the late 60s to describe those movies.

So what were the characteristics of a Pink Film? First of all, the average Pink Movie featured a certain quota of sex scenes, with no footage of genitalia, for censorship reasons. It was usually shot within a week, compared to the four weeks needed for a typical program picture, and was about an hour-long.

As most Pink productions had no studios available to film at, the only option was to make use of outdoor locations. The movies were shot clandestinely, since the crew rarely applied for location permits. Lastly, the target audience consisted of young men, who went to the cinema to satisfy their desire for on-screen sex.

Even though the free expression of sexuality in Pink Films could be regarded as an act of resistance against the oppressive and censoring regime of 60s Japan, the main reason for their appearance is financial. According to Pia D. Harritz, pink movies were less a product of political intentions to “liberate” sex or promote women’s rights and more of a way to attract new audiences. Since cinema attendance had dropped dramatically in 1962, the response of the industry was the production of those lucrative, low-budget movies.

The First Generation of Pink Filmmakers (1962-1971)

The First Pink Movie by Satoru Kobayashi

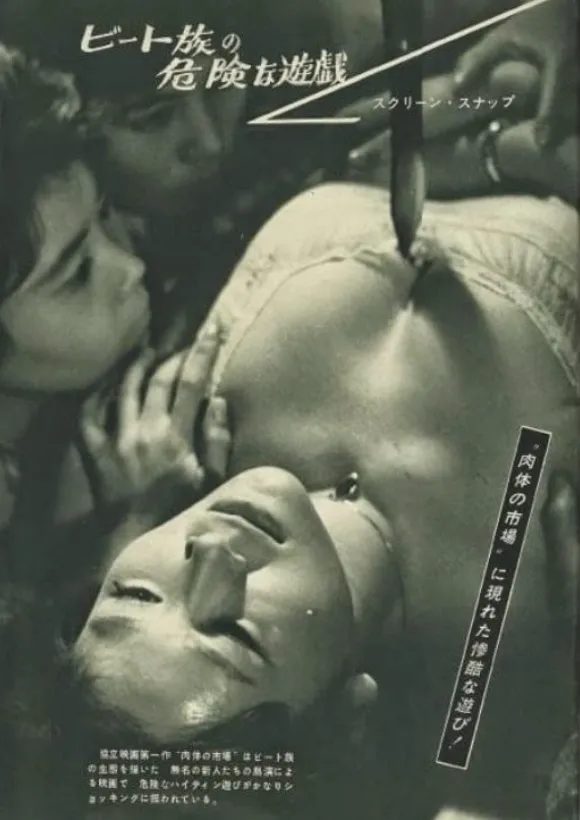

Flesh Market directed by Satoru Kobayashi initiated the first wave of Pink Movies in 1962. The 49-minute film was starring Tamaki Katori, one of the most prolific Japanese adult film actresses of the 1960s, in the role of a young girl captured by criminals while investigating the mysterious suicide of her sister.

Flesh market’s poster (photo: imdb.com)

The movie’s display of nudity and sex led to the confiscation of all the prints and the original negative by the Metropolitan police, only two days after the movie’s opening. However, the film producers reacted immediately by reassembling a new version of the film and removing most of the offensive scenes. After these alternations, the film was released again and turned out to be a huge box office success, grossing over 100 million yen on a budget of just 8 million yen. Nevertheless, only speculations can be made about the exact content and qualities of the movie, since all that remains of the film today is a 21-minute fragment along with a few written accounts.

Pink Movies in the Spotlight After His Trial: Tetsuji Takechi

After producing influential and innovative kabuki plays, Takechi turned from stage to the film industry to pursue a career as a Pink director. In the span of three and a half decades, he directed 13 films. His first film A Night In Japan: Woman, Woman, Woman Story (1963), a sex-documentary focusing on the nightlife of Japanese women, was produced independently and released both in West Germany and in the US. However, two of his films made a sensation at that time: Daydream (1964) and Black Snow (1965).

Daydream was the first big-budget, mainstream Pink Film released in Japan. Due to its depiction of female nudity, it was also the first film to undergo “fogging” or in Japanese “bokashi” (a form of censorship used to hide sexually related images and scenes), a common element in Japanese erotic cinema until this day.

Black Snow brought Takechi and Pink Movies in the spotlight of public discourse over matters of censorship and artistic oppression. After the release of his film, Takechi was arrested on indecency charges, with his trial becoming a public battle over censorship between Japan’s intellectuals and the government. Takechi won the trial, while its publicity played an important role in the future of Pink Movies’ production and recognition.

The Master of Pink Movies: Koji Wakamatsu

Usually referred to as the master of Japanese Pink Film, Koji Wakamatsu made his move into the production and direction of Pink Films in the early 1960s partly inspired by the success of Takechi’s Daydream.

Wakamatsu’s movies were usually produced for less than 1 million yen (about $5.000) and, like most Pink Movies, were often shot in one location, sometimes in his office or on the rooftop of the building, using natural lighting, and single-takes. His early films were usually black and white with occasional bursts of colour, which did not serve narrative purposes but were more of theatrical effects.

For the most part of his career, he stayed away from big studios to have the greatest possible artistic freedom over his work. In 1965, he created his own production company, the Wakamatsu productions.1 His name became known beyond the Pink Film industry after the international uproar following the entrance of Affairs within walls (1965) into the 15th Berlin International Film Festival and its dismissal as a national disgrace in Japan. After Affairs within walls, Wakamatsu established an extremely prolific career, which included co-producing Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses(1976).

Koji Wakamatsu by Kris Dewitte (photo: bfi.org.uk)

What distinguishes the works of Wakamatsu from other uninspiring exploitative directors is not only his technical skills but also his approach towards sensitive topics like rape and violence, which he used in order to make a larger, usually social or political point.

His Go, Go, Second Time Virgin (1969), a lyrical poem that has nothing to envy of Godard’s long dialogues on life and art, features a scene that openly criticizes the Japanese pornography industry’s obsession with rape. Talking to another person but clearly addressing the audience, which for a Pink Film in Japan would be predominantly male, the protagonist says: “My mother was gang raped and then she gave birth to me. Are the tears we two shed when raped, the tears women shed? What tears? What sadness? I’m not a woman. (…) I’m not sad at all” and concludes with a loud “Fuck you.”

Directed 200 Films and Produced 500: Kan Mukai

Like Wakamatsu, Kan Mukai moved to the emerging Pink Film genre in the mid-1960s due to the genre’s increasing popularity and revenue. His first film Flesh (1965), a loosely related series of scenes in the life of a prostitute, established him in the genre thanks to his impressive technical skills.

According to some Japanese sources, Mukai was the first director to use S&M as the primary subject of the film Sexy Partners (1967), while his Blue Film Woman (1969) was one of the first Pink films to be shot in colour widescreen. Blue Film Woman was praised for its stylization and psychedelic aesthetics consisting of sexy images of naked women, colour filters on the lights, strobe effects, and funk music.

Mukai enjoyed a more productive career than Wakamatsu, as he directed 200 films and produced about 500 pink, action, and more mainstream films. Commenting on Mukai’s outstanding cinematography and film aesthetics, a critic for Kinema Junpo (Japan’s oldest film magazine) once wrote that “Mukai is the only genre director who could rival Koji Wakamatsu.”

Other Pink Directors: Koji Seki and Sojiro Motoki

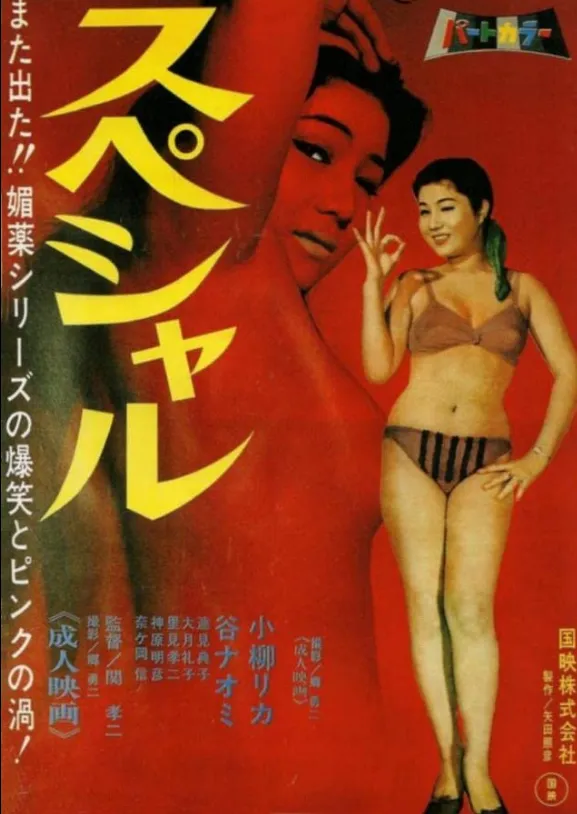

Koji Seki (or Takashi Seki) made his directorial debut in 1963 with the Valley of Lust, filmed in the same year as Satoru Kobayashi’s Flesh Market. He directed Noriko Tatsumi, the “Queen” of Japanese soft-core sex movies from 1967 through 1970, in some of her best-known films, like Whore (1967) and Erotic Culture Shock: Swapping Partners (1969). He also directed Naomi Tani, a dedicated S&M actress, in her film debut Special (1967). His 1968 film Invisible Man: Dr. Eros was the first Pink Film with an “invisible man” theme and inspired three sequels.

Koji Seki directed Naomi Tani, the “S&M Queen” in her film debut Special (1967). (photo: imdb.com)

Sojiro Motoki, besides being a known producer behind many classic titles from the 50s, including Seven Samurai (1954), Ikiru (1952), and Throne of Blood (1957), was a very active Pink filmmaker from 1962 until his death. Within the span of 15 years, he directed 111 films, under different pseudonyms (Takeo Takagi, Shoji Shinagawa, Keiichi Kishimoto, Junji Fujimoto). With little to no information available on his work, we can only be partly aware of Motoki’s contribution to the genre.

The Post-First Wave Period

While in the 1960s Pink Films were mostly made by small, independent studios, during the 1970s some major Japanese studios took over the already thriving Pink Films industry.

In 1971, Nikkatsu, the oldest studio in the country, launched its own brand of Pink Movies, the Roman Porno series. The series became popular both with audiences and critics for its high production values and recognizable talent. Even though the Pink Film production was afflicted in the 80s by the AV industry, films of the genre are still being produced, largely thanks to a strong network of production, distribution, and exhibition.

1 In 1966, many young talents joined Wakamatsu productions among which was Masao Adachi, a screenwriter best known today for his writing collaborations with Wakamatsu and Nagisa Oshima. Adachi brought to Wakamatsu’s films a much closer relationship with the Japanese far left, which culminated in Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), a propaganda documentary co-directed by Adachi and Wakamatsu as a Japanese contribution to the Palestinian guerrilla movement.

Sources

Domenig, Roland (2002) Vital flesh: the mysterious world of Pink Eiga

Grossman, Andrew (2002) The Japanese Pink Film: Tandem, The Bedroom, and The Dream of Garuda on DVD

Harritz, D. Pia (2007) Consuming the Female Body: Pinku Eiga and the case of Sagawa Issei

Sharp, Jasper (2008) Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema, Fab Press Limited

Toscano, Alberto (2013) Walls of Flesh: The Films of Koji Wakamatsu (1965–1972), Film Quarterly 66(4):41-49

Read also: A Century-Old Porn: The Story Behind 3 Stag Films